Top 20 memories as a postdoc

Now that I finished my training, I figured I’d share the best memories/moments/experiences/lessons/stories during my time at the Scripps Research Institute. The postdoc lyfe is tough the whole way through, so I wanted to wait until things settled down before looking back. Cover art is a group photo taken at my farewell party in the lab.

Still blogging thru it all

“It was the best of times [scientifically]; it was the worst of times [financially]”

I started this website 5 years ago in the middle of my PhD, and it’s cool to look back and reflect. I’m not gonna say the feelings of imposter syndrome from undergrad are gone, but they’re much easier to dismiss today. Just look at the data: if getting into USC, publishing three 1st author papers, and passing my defense was luck, does getting to the Scripps Research Institute by accident make sense? The place with back to back Nobel prize winners made a mistake? No, that’s cap.

I wrote about the good and wrestled with the bad; not for clout but because I thought it might help someone else going through it. Even now, I’ve learned a lot about how to position yourself for success when making the transition from academia to industry, and I plan on writing a post on things I wish someone told me; to make the process easier for others.

Speaking of which: I still plan on blogging/posting after I get an industry job. Obviously I’m not going to be disclosing confidential or proprietary information, but this is fun for me. Say I were to get a job at a company developing a biologic so all biologic are off the table; I’d blog about med chem and small molecules, or breakdown a method I think is cool, or blog about my regulatory training, but for sure write more cloning freestyles. I might even include hobbies, like mopeds (my Yamaha QT50!) or cars (my 1986 Z31!)

Anyway, drug science is dope, I care about it all, and I look forward to continued blogging.

Pitching to investors at Nucleate’s San Diego showcase

As a postdoc, I felt like testing my business and regulatory science skills, so I joined Nucleate’s San Diego activator program as a business applicant and volunteered my time at a startup spinning out of the Salk Institute. It was a hardcore and intense time: on top of the papers and projects, I was the commencement speaker for my community college! Literally two days after I got back from Kansas, we had the pitch, which was stressful but in the end all the effort paid off. Our team pitched the company to the San Diego venture capital community and won the Alnylam Scientific Excellence award.

I ended up going a different route with my career, but using my regulatory science skills and being part of a team trying to bring treatments to patients while also being a full-time postdoc is kinda crazy. Plus, I made a lot of connections in the San Diego biotech scene, which was one of my original goals, which was dope.

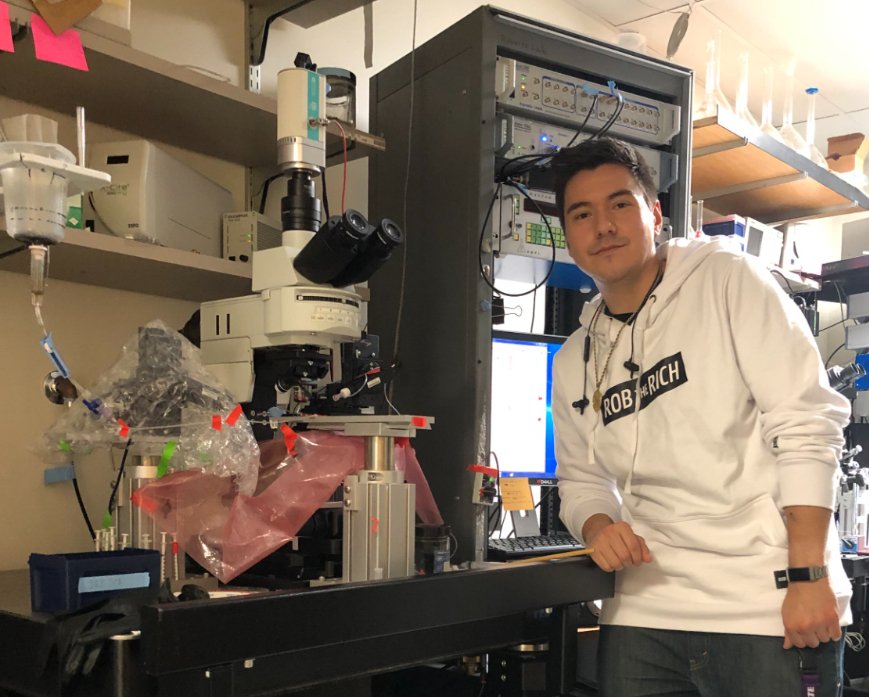

Learning patch-clamp electrophysiology

I’m proud to call myself a patch-clamp electrophysiologist but I gotta say: I’m conflicted about this one. I made a decision to augment my molecular biology and cell-based training, but most don’t understand my [ridiculously] technical and niche skills. Why? Probably because the skills are too technical and niche to be recognized and translated broadly. I understood why, but I was still tight about it. So, rather than be bitter, I figured get better at showing what I did.

IIRC: Recording sIPSCs in the CeA of dependent female SD rats while listening to J. Cole’s Truly Yours 2 EP.

That why I made sure to recorded myself doing electrophysiology experiments in the lab before I left. My two goals were: 1) to produce a time-lapse video to show people what it is that I do, and 2) for instructional and teaching purposes (coming soon!) Plus, electrophysiology is cool, and every time I come across an old photo or video from lab, it makes me smile and brings me back to what I was doing at the time.Anyway, the take-home is that other people’s appreciation (or lack-thereof) doesn’t add or take away from the fact that I can learn something insanely difficult and produce publication-quality data. If I wasn’t sure about my abilities at the end of my PhD, I’m confident in them after doing a postdoc in the Roberto laboratory.

To put it another way: I learned to record the activity of neurons, which proves I can learn any skill or technique I put my mind to, and like Jay-Z said: if you can’t respect that, your whole perspective is whack ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Not being the only (other) Latino scientist

I met 3 other latino/a postdocs doing alcohol research at Scripps; that’s amazing! As an undergrad and during my PhD, it felt like there was a limit to the number of latinos in STEM (in my experience, 2). It might sound like slow progress, but it’s welcome . I also met a latina professor at Scripps! That was huge for me! I enjoyed my time at K-State and USC, but I was always wondering “where are the professors that look like me?” I can say I met more Hispanic and latino/a scientists at Scripps than ever before and that’s a W.

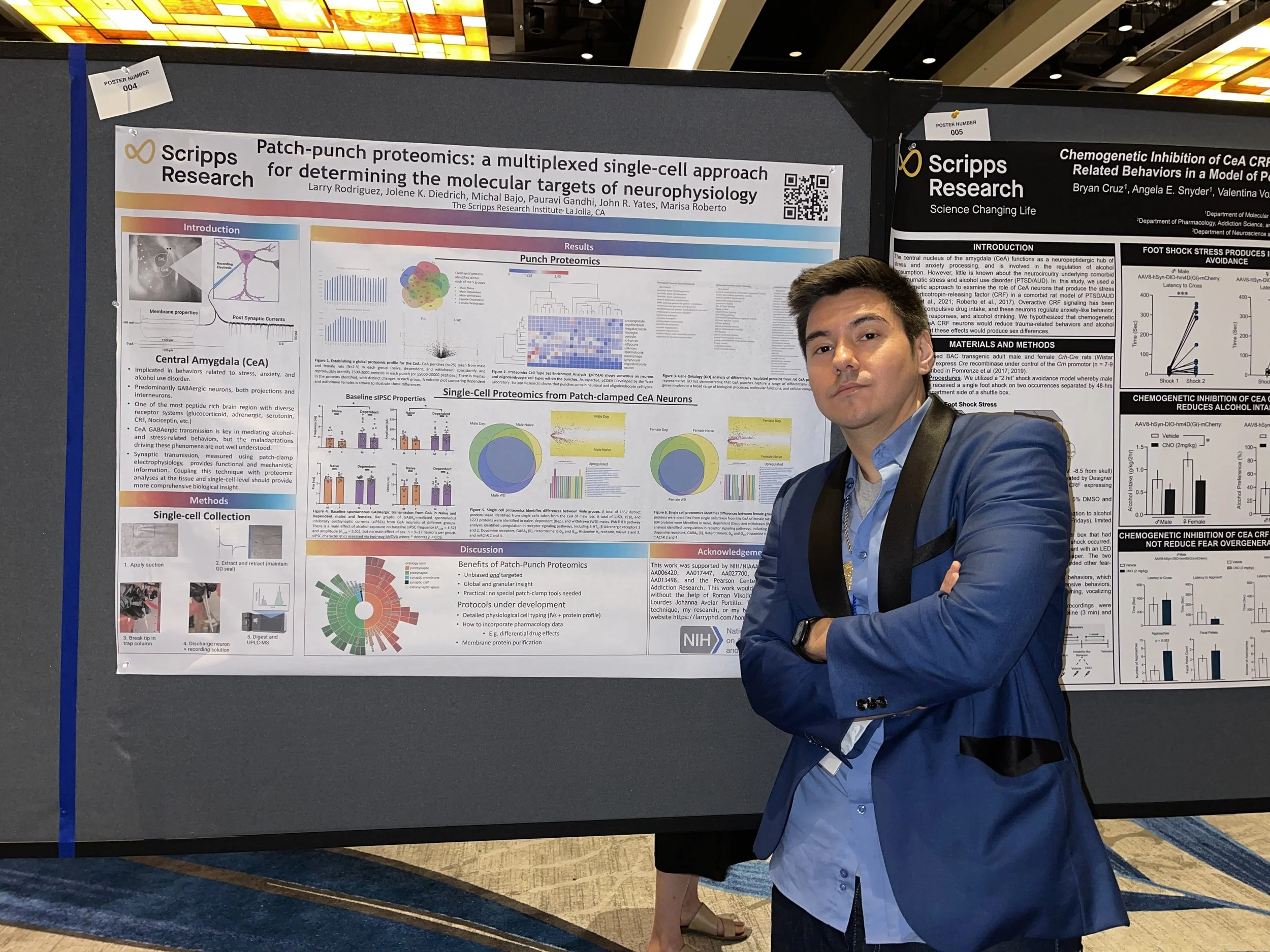

RSA 2022

RSA 2022 was a movie for real! I wrote about it before, but it’s worth repeating: it means a lot to have my training come full-circle. Some context: in 2016 I emailed my PhD advisor about wanting to do patch-seq after reading a review on the topic, which was way outside the scope, capability, and interest of my PhD advisor’s laboratory. Even though I learned to love working with frog eggs, patch-clamp is the gold standard in ion channel drug discovery, and I wanted to apply my molecular skills to answer tough questions. This led me to Scripps, where as I postdoc 6 years later I presented patch-punch proteomics: a (cooler imo) method that combines single-cell and bulk proteomics with electrophysiology. No one is doing this or pushing things to where we are, and the fact that I can honestly say I took a leading role in the collaboration is crazy.

Getting rejected from the BWF PDEP and the Vertex Fellows Program

Rejection sucks; how could that be a top moment?? In the case of the BWF PDEP, I was told my proposal was in among the finalists considered for an award, and even though I didn’t get it, I gave it a shot. Besides, after 2 years I can honestly say that everything in the proposal still important and was accomplished, or will be soon. In the case of the Vertex Fellows program, again I was a finalist but not a winner, and I have to conclude that this was the best possible outcome. How? It meant that I could move in support of my partner’s postdoc like she supported me when I first moved to San Diego. Today I find myself as a free agent in the bay area (biotech capital of the world??) and I get to be choosy about the next step in my career; if it wasn’t already up for me (see Investing), it will be.

Trusting my intuition (subconscious triage)

It sounds weird but I have great science intuition. That means I have use my broad knowledge of biochemistry, molecular biology, and receptor pharmacology to rapidly identify promising opportunities. Sounds like word salad, but it’s not. The example I always go back to is the single-cell proteomics project. Rather than prioritizing sample collection (and stalling all other projects) I made sure to make progress on both the collaboration and the various projects in the lab. Additionally, I knew from the preliminary data that biological function would be a huge challenge because patch-clamp electrophysiology measures network activity, which would be congruent to tissue-punch proteomics rather than single-cell analysis. So, I decided to do it all: record from neurons just like I would during a typical pharmacology study, then try to collect the neuron at the end of an experiment, then take a punch of the brain region of interest. In this way, we optimize data generation across each project without sacrificing anything. At the time, it was a low-risk high-reward, because worse-case scenario: I was wasting a PCR tube and 3 minutes of my time. The risk paid off big time, because it turns out you can run a typical electrophysiology experiment without affecting the number of peptide/protein hit.

Traveling to Italy in 2021

My favorite piece: The Atlas. Big postdoc vibes.

I was vaxxed, boosted, and finished with data collection in late 2021, so I decided to accompany my girlfriend on her trip to Italy for a conference. Pandemic or not, I’ve never enjoyed the process of traveling, but our Japan trip during grad school was amazing, so I figured I’d go for it. We did a lot, and Florence was definitely the highlight of the trip: lots of art, lots of food, lots of culture. Plus, lots of love/respect for mopeds (Vespas really, but close enough). I found a way to get my workouts in, and funny story: our team actually gave the pitch to join Nucleate while I was in a business office in Florence.

One of the highlights was touring the Michelangelo museum. I would not call myself an art aficionado but I do love visiting museums. I never really got into art history, but our guide Elvis Zgura (I highly recommend his tours!) broke everything down which provided amazing context for each piece and gave me a whole new appreciation for renaissance-era artists. Michelangelo’s unfinished works were probably my favorite, just because I identified with trying to “escape from the marble.” David having different expressions/meanings depending on your perspective was also kind of mind-blowing, as if it wasn’t a technically amazing feat already. Also, I’m a WSG fan, so seeing other works by Caravaggio in person at the Uffizi gallery was a vibe. Lastly, I tried lots of different foods, and discovered that I love chicken liver tartare.

This is a long-winded way to say that Tyler, the creator and DJ Drama were right on Call Me If You Get Lost; you should definitely travel the world.

Thinking, questioning, and following the science

Both philosophically and scientifically: I ask questions I want the answer to. Scientists face pressure to to know everything, and if a protocol works but you don’t know why, you may not want to question it. If it’s not working though, you better figure out why. As an undergrad, a big part of imposter syndrome came from not knowing how a particular experiment worked. I’m talking about what’s in the buffer and why; will forgetting a mixing/spinning step kill your results? How do you find out why something isn’t working? Only after grad school did I learn how to triage failure modes and identify clues from unsuccessful experiments.

In this context, it makes sense why electrophysiologists may be superstitious; you’re under a lot of pressure to get data from your brain slice before all the neurons die, and even an experienced, hardcore electrical engineer would agree that troubleshooting takes time. You really don’t want to think about why a random noise occurs once every so often. Still, there were important times where I wouldn’t let certain questions go, and it cost me very little in productivity and resources to get to the answers.

Osmolarity of ice samples (I) and liquid samples (L) for two different brain regions. Immediately after the brains have been dissected, we put them into a liquid-ice slurry, and since the ice floats, the brain region is seeing a shockingly hypotonic solution (the ideal range is 290-310 mOsm/kg H2O.)

The smallest and best example of this is when our group began splitting the brain and recording from a new region. The protocol usually worked well for the central amygdala (CeA), but the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) was uniquely problematic. We discussed the most likely cause (the high sucrose aCSF cutting solution; HS-aCSF) but it was always in the right range (and the CeA worked!) so what was going on? Since we cut the brains in an ice slurry, I figured why not test the slurry right before it reaches the brain, and sure enough, there was a big difference in the osmolarity (>90 mOsm/kg H2O). It made sense that the amygdala, which was mostly inhibitory/GABAergic was less sensitive to changes in osmolarity compared to the cortex, which had more Glutamatergic cells (possibly leading to excitotoxicity). What was causing the change though? After surprising a close colleague with the data (he couldn’t believe it at first), we came to the conclusion that yes, the osmolarity of the HS-aCSF was correct from the beginning to freezing, and the freezing process didn’t cause the dramatic change in osmolarity. However, when you prepare the ice slurry, it’s not a perfect mixture, and it’s possible for the ice to melt and refreeze without the salts. This explains the difference in osmolarity and why it was only affecting the new region, which was more sensitive to these effects.

Seriously, it was a super small experiment: measure the osmolarity of the HS-aCSF as a solution and as a crushed but frozen solid, separately and after mixing. However, it got straight to the point, it was easy/low-risk, and it was super fun! My colleagues and I had fun doing an experiment inside an experiment, and again the discrepancy was a huge surprise but made perfect sense when we thought about it.

I also have to mention one of the more memorable discussions I found myself in: what is the role or “job” of a postdoc? I believed that a postdoc was paid to think deeply and critically, to solve problems, and to learn new things. Someone else thought that a postdoc is paid to generate data; if thinking was to be done, it should be done outside of lab hours, during personal time. We agreed to disagree, and I could at least understand how one could reach that conclusion (publish or perish mentality). I told this person to follow my blog to see how thinking works out for me, so we shall see!

Making time for family

During my PhD, I wrote about how I wished I spent more time with family. During my postdoc, I made sure to take the opportunity to see family whenever I could. That sounds hard when you have dozens of projects to complete and animal experiments to prioritize. On the other hand, if it never feels like it’s a perfect time for a break, then take a break/vacation when you feel the need to. As important as science may be, I don’t think you have to sacrifice spending time with loved ones. There’s still a few events I wish I could have attended, but I can say that I made progress towards a sustainable balance between work and family life, which is good.

Community

Community is a key part of doing good science, be it in-person or virtually. I learned that during my PhD and it was reinforced during my time as a postdoc. During the worst of times, commiserating about science with colleagues helps you brush off the stress. Plus, even if you’re a postdoc who works non-stop because all your experiments magically work out; you probably aren’t going to remember the many thousands of hours you spent in the lab. What you will remember are the other scientists you got to know, possibly over free food and beer, especially if you’re at Scripps and have beautiful views of the ocean from any point on campus.

the Scripps Research environment

The Scripps Research Institute is hardcore and people know it. My advisor’s lab included 3 staff scientists, 6-8 postdocs, and dedicated research technicians working with each other and on our respective projects. I will say that I missed mentoring undergraduate students (Scripps is a research non-profit with only a graduate degree granting program), but with that came a certain level of speed and intensity. Everyone was extremely smart and ridiculously capable, which makes me think of the Drake bar “transitioning from fitting in to standing out”. That transition is part of the postdoc experience, but doing it at Scripps is a little different. IYKYK.

Earning the title of Distinguished Alumnus from my college

I’m trying to figure out if I’m the youngest and the first latino alumnus to earn distinction from my community college, but in any case, I’m honored. My dream has always been to use science to do good, and getting recognized by the community that played a huge role in my success is dope. Making my family proud though? That hits different. Anyway, I’m just barely getting started with my career and I’m looking forward to giving back even more, so be sure to check back soon!

Hating animal research (but doing it anyway)

I didn’t have to do a postdoc to learn I didn’t enjoy working with animals; this became clear to me in grad school when I traveled to the UIC to learn extracellular slice electrophysiology. Still, I knew that in vivo animal studies were important in getting a drug into clinical trials, and discomfort didn’t justify avoiding this area of research. In fact, I came to the opposite conclusion: because I loved working with in vitro and cell-based assays, I needed to work within a group using ex vivo techniques. My reasoning: if you’re going to do something, it better have an impact, and what’s more impactful than facing fears and overcoming obstacles?

The learning curve was steep, but I learned to get over my discomfort. In the end, I got comfortable with neuroanatomy and identifying different brain regions, which was a huge insecurity during my PhD. It’s important to know that I have never taken a single neuroscience class ever; that’s why I tell people I’m a biochemist turned neuroscientist. I don’t know what field I’ll end up in next, I just know nothing will stop me.

Improving consistently

I feel like consistency is one of my superpower. I took me a few weeks of consistent failure to learn ephys, and once I did, I was always looking for the next challenge. The same idea applies to everything else in my life: I decided I wanted to add running to my workout routine, and I cut my mile times down several minutes. I also picked up cooking; at first because the UTC area felt like a food desert during the early days of the pandemic, then as a personal challenge during the holidays. Plus, I dethroned Kraft’s Flamin’ hot mac and cheese as my 12 year old brother’s favorite food; that title belongs to the Kitchenista’s baked mac and cheese recipe. See also: blogging, investing, journaling (for mental health and to keep track of cool papers I’ve read), and publishing.

Seeing success in a Team

Patch clamp electrophysiology is kinda solitary, and the sooner you become independent, the sooner you will generate data. However, it can also be repetitive and tedious. I can say that I’ve tried the whole solo-science thing, and while it worked out, the memories and lessons that stick out come from working in a team. I like to say that if you’ve patched one cell, you’ve patched them all, so I never felt like I couldn’t help someone with their project because mine was more important; to me the important part was finishing projects, so I regularly found myself volunteering to help out others with projects (BNST, mPFC, hippocampus, whatever). Plus, everything moves faster when you’re working in a well organized group and you end up learning a lot more.

Also, if you don’t know the importance of communication and teamwork, being in an electrophysiology group will quickly teach you. If you’re having a tough day (i.e. you’ve been trying to patch cells for over an hour with no results) the best thing to do is to talk to other members of your team. Maybe everyone is having trouble so you should regroup and try to troubleshoot together. Maybe another brain region or slice seems fine, and you just pulled a dead slice (it happens). Maybe your internal solution went bad and you can try borrowing someone else’s. Personally, I would never want to be the only electrophysiologist on a team, and while Scripps was very much a hardcore environment, I missed teaching and working with a team undergraduates in the lab. The good thing is, industry provides opportunities to mentor junior scientists and places an emphasis on teamwork, which is what I’m looking forward to in the future.

Investing

I always saw my postdoctoral training as an investment in myself, and for the most part, my effort has either paid off or is in the process of paying off. I will say that you go through it. In fact, when you’re going through it, it does not feel worth it. I can’t tell you how many times I had to explain my decision to do a postdoc to friends and family. Self-awareness is key when deciding to do a postdoc (really, everything in life) which is why asking “should I do a postdoc” is a question that others can’t answer for you.

Now, if you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know I like to talk about **NOT FINANCIAL ADVICE** money, which is not compatible with the postdoc lyfe! Postdoc salaries are (still) depressing, but thanks to some clever investments, its up for me. I don’t care what the stock market says, I can chill** for years, and that’s a pretty dope feeling. Add being 1st gen to the mix, remember what I’ve said about PhD and postdoc stipends, and it becomes a remarkable flex. In the same vein, I made it this far by staying two steps ahead of the game, hustling smart, being self-aware, and always playing the long game. The marathon continues (RIP Nipsey Hussle).

Always finding the funny

Everyone I’ve worked with will tell you the same: Larry is funny. Comedy relieves stress, keeps things humble, and is a creative outlet. The best feeling in the world is seeing a joke completely change someone’s demeanor in lab when they’re having a tough day. Whether it’s soggy pizza, lifting the curse of the preprint, or putting frog statues and Pokemon all over my bench; if I’m involved, I’m going to find a way to get a good laugh out of the things, no matter how crazy the situation.

Standing in who I am

Vol. 2... Hard Knock Postdoc Lyfe

I’m not sure if it’s clear from this blog, but I have a unique personality, which makes the way I do science unique. It’s a combination of a lot of things (that I’ve talked about): my sense of humor, my background, my opinions on science, my ethics/morals/values, and my career goals. Postdocs go through a lot for many reasons, and I can honestly say that I came out of it a stronger, better, and more concentrated version of myself.

Ending my training and moving on

Regardless of what you want to do, the point of doing a postdoc is to find a job. Traditionally***, that would be a tenure-track faculty position. However, I have always wanted to go into industry, and my partner was offered an amazing career opportunity in the Bay area, so I decided it was the time to move, whether I already had job lined up or not. Drake summarizes the vibes on The Remorse: “As soon as I left I had to make peace with that/Dropped out of school 'cause nobody was teaching that”

Anyway, I tell people that I’m unafraid of the unknown, and my actions back it up. Just give it time, we’ll see who’s still around a decade from now.

* setting stop-losses will save you if you let them; that goes for finances, projects, relationships, everything in life tbh #NoSunkCost #CostHasSunk

** I’m incapable of only chilling, even as I’m in the transition period between academia and industry

*** Statistically unlikely tho